The Great Gildersleeve (1941–1957),

initially written by Leonard Lewis Levinson,[2] was one of broadcast

history's earliest spin-off programs. Built around Throckmorton

Philharmonic Gildersleeve, a character who had been a staple on the

classic radio situation comedy Fibber McGee and Molly, The Great

Gildersleeve enjoyed its greatest success in the 1940s. Actor Harold

Peary played the character during its transition from the parent

show into the spin-off and later in a quartet of feature films

released at the height of the show's popularity.

On Fibber McGee and Molly, Peary's Gildersleeve was a pompous

windbag who became a consistent McGee nemesis. "You're a

haa-aa-aa-aard man, McGee!" became a Gildersleeve catch phrase. The

character was given several conflicting first names on Fibber McGee

and Molly, and on one episode his middle name was revealed as

Philharmonic. Gildy admits as much at the end of "Gildersleeve's

Diary" on the Fibber McGee and Molly series (10/22/40).

He soon became so popular that Kraft Foods — looking primarily to

promote its Parkay margarine spread — sponsored a new series with

Peary's Gildersleeve as the central, slightly softened, and slightly

befuddled focus of a lively new family.

Premiere

Premiering on NBC on August 31, 1941, The Great Gildersleeve moved

the title character from the McGee's Wistful Vista to Summerfield,

where Gildersleeve now oversaw his late brother-in-law's estate and

took on the rearing of his orphaned niece and nephew, Marjorie

(originally played by Lurene Tuttle and followed by Louise Erickson

and Mary Lee Robb) and Leroy Forester (Walter Tetley). The household

also included a cook named Birdie. Curiously, in Fibber,

Gildersleeve occasionally speaks of his wife; his change to a

bachelor is something of a discontinuity. He even states on occasion

that he has never been married.

In a striking forerunner to such later television hits as Bachelor

Father and Family Affair, both of which are centered on well-to-do

uncles taking in their deceased siblings' children, Gildersleeve was

a bachelor raising two children while, at first, administering a

girdle manufacturing company ("If you want a better corset, of

course, it's a Gildersleeve") and then for the bulk of the show's

run, serving as Summerfield's water commissioner, between time with

the ladies and nights with the boys. The Great Gildersleeve may have

been the first broadcast show to be centered on a single parent

balancing child-rearing, work, and a social life, done with taste

and genuine wit, often at the expense of Gildersleeve's now slightly

understated pomposity.

Many of the original episodes were co-written by John Whedon, father

of Tom Whedon (who wrote The Golden Girls), and grandfather of

Deadwood scripter Zack Whedon and Joss Whedon (creator of Buffy the

Vampire Slayer and Firefly).

The key to the show was Peary, whose booming voice and facility with

moans, groans, laughs, shudders and inflection was as close to body

language and facial suggestion as a voice could get. Peary was so

effective, and Gildersleeve became so familiar a character, that he

was referenced and satirized periodically in other comedies and in a

few cartoons.

Family

Aiding and abetting the periodically frantic life in the

Gildersleeve home was family cook and housekeeper Birdie Lee Coggins

(Lillian Randolph). Although in the first season, under writer

Levinson, Birdie was often portrayed as saliently less than bright,

she slowly developed as the real brains and caretaker of the

household under writers John Whedon, Sam Moore and Andy White. In

many of the later episodes Gildersleeve has to acknowledge Birdie's

commonsense approach to some of his predicaments. By the early

1950s, Birdie was heavily depended on by the rest of the family in

fulfilling many of the functions of the household matriarch, whether

it be giving sound advice to an adolescent Leroy or tending

Marjorie's children.

By the late 1940s, Marjorie slowly matures to a young woman of

marrying age. During the 9th season (September 1949-June 1950)

Marjorie meets and marries (May 10) Walter "Bronco" Thompson

(Richard Crenna), star football player at the local college. The

event was popular enough that Look devoted five pages in its May 23,

1950 issue to the wedding. After living in the same household for a

few years with their twin babies Ronnie and Linda, the newlyweds

move next door to keep the expanding Gildersleeve clan close

together.

Leroy, aged 10-11 during most of the 1940s, is the all-American boy

who grudgingly practices his piano lessons, gets bad report cards,

fights with his friends and cannot remember to not slam the door.

Although he is loyal to his Uncle Mort, he is always the first to

deflate his ego with a well-placed "Ha!!!" or "What a character!"

Beginning in the Spring of 1949, he finds himself in junior high and

is at last allowed to grow up, establishing relationships with the

girls in the Bullard home across the street. From an awkward

adolescent who hangs his head, kicks the ground and giggles whenever

Brenda Knickerbocker comes near, he transforms himself overnight

(November 28, 1951) into a more mature young man when Babs Winthrop

(both girls played by Barbara Whiting) approaches him about studying

together. From then on, he branches out with interests in driving,

playing the drums and dreaming of a musical career.

Neighbors and friends

Outside the home, Gildersleeve's closest association was with the

cantankerous estate executor Judge Horace Hooker (Earle Ross), with

whom he had many battles during the first few broadcast seasons.

After a change in scriptwriters from Levinson (August 1941 to

December 1942) to the team of Whedon and Moore in January 1943, the

confrontations slowly subside and a true friendship slowly blossoms.

In an early episode, Throckmorton was given the key of the city to

Gildersleeve, Connecticut, a village in the town of Portland,

Connecticut.

Joining Throckmorton's circle of close acquaintances during the

second season (September 1942) are Richard Q. Peavey (Richard

LeGrand), the friendly neighborhood pharmacist, whose nasal-voiced

delivery and famous catchphrase, "Well, now, I wouldn't say that!"

always elicited giggles from the studio audience (and was frequently

quoted in animated cartoons such as 1945's Draftee Daffy); and Floyd

Munson (Arthur Q. Bryan), the rough-around-the-edges neighborhood

barber.

Munson was played by Mel Blanc in at least two episodes of the first

season: coincidentally, Bryan was the originator of the voice and

character of Elmer Fudd, the one voice which Blanc never thought he

had made his own. Blanc appeared frequently in other episodes,

uncredited, often voicing two or more supporting characters:

deliverymen in "Planting A Tree" and "Father's Day Chair" also

"Gus", a petty crook in the latter; a radio station manager and a

policeman in "Mystery Singer" are a few.

In the fourth season, (October 8, 1944) these three friends, along

with Police Chief Donald Gates (Ken Christy), form the nucleus of

the Jolly Boys Club whose activities revolve around practicing

barbershop quartet songs between sips of Coca-Cola.

Adding spice to Gildersleeve's life are the women who come and go:

the Georgia widow Leila Ransom (Shirley Mitchell), who leaves him at

the altar on the last show of the 1942-43 season (June 27, 1943),

and the school principal Eve Goodwin (Bea Benaderet), who was

another close call at the altar of matrimony (June 25, 1944). After

almost being trapped a third time (1948-49 season) to Leila's cousin

Adeline Fairchild (Una Merkel) Throckmorton learns his lesson and

makes sure his future involvement with women is much more

circumspect. He dates the sisters of his surly neighbor from across

the street, Ellen Bullard Knickerbocker (Martha Scott) and Paula

Bullard Winthrop (Jeanne Bates), as well as Nurse Katherine Milford

and school principal Irene Henshaw (both played by Cathy Lewis) in

an on-and-off fashion over many years, making sure the situation

doesn't progress beyond the just friends state (although he's always

after that special kiss).

To add adversity to Gildersleeve's world is the aforementioned surly

neighbor from across the street: the retired millionaire Rumson

Bullard, after initial portrayals by another actor, was portrayed

definitively by Gale Gordon, who was more pompous than the earlier

version of the Gildersleeve character. Bullard was the focus of a

continuity error: he began as a happily married man with two

children and inexplicably became a widower with sisters and nieces

living with him periodically. In numerous episodes, Mr. Bullard

alternates between being chummy with "Gildy" (in order to get

something he wants) to calling him a "nincompoop water buffalo". The

two often court the same women (particularly Katherine Milford).

Decline and fall

Beginning in 1950, the show's momentum changed as the legendary CBS

talent raids of the time began to take their toll. The most painful

result of the raids was the jump of Jack Benny and Burns and Allen

to CBS, forcing NBC to offer more lucrative deals to Bob Hope, Phil

Harris and Alice Faye in order to keep them from defecting. Harold

Peary was convinced to move The Great Gildersleeve to CBS, but

sponsor Kraft refused to sanction the move. Peary, now contracted to

CBS, was legally unable to appear on NBC as a star performer, but

Gildersleeve was still an NBC series. This prompted the hiring of

Willard Waterman as Peary's replacement. Peary, meanwhile, began a

new series on CBS which was a rather obvious attempt to reproduce

the Gildersleeve show with the names changed. The Harold Peary Show,

lasting a single season, included a fictitious radio show within the

show. This was Honest Harold, hosted by Peary's new character.

Waterman and Peary were longtime friends from Chicago radio;

Waterman had replaced Peary as the Sheriff in The Tom Mix Ralston

Straightshooters in the 1930s. His voice was a near-perfect match

for Peary's, though he refused to use Peary's signature laugh. Peary

reportedly sued unsuccessfully to retain the right to both the

Gildersleeve character and vocalisms, but Waterman agreed with Peary

that only one man held the patent on the Gildersleeve laugh.

Starting in mid-1952, some of the program's long time characters

(Judge Hooker, Floyd Munson, Marjorie and her husband) would be

missing for months at a time. In their place were a few new ones

(Mr. Cooley, the Egg Man, and Mrs. Potter the hypochondriac) who

would last only a month or so. By 1953, Gildy's love life took

center stage over that of his family and friends. His many love

interests were constantly shifting, and women were coming and going

with such frequency that the audience had a hard time keeping up.

His adversary, meanwhile, shifted from Mr. Bullard, who disappered

completely from the cast of characters, to Dr. Clarence Olsen

(George N. Niese).

1954 saw a drastic change in the show's format. After missing the

fall schedule, it finally appeared in November as 15-minute episodes

that aired five times a week, Sunday through Thursday from 10:15 to

10:30pm Eastern, immediately following the quarter-hour version of

Fibber McGee and Molly. Only Gildy, Leroy and Birdie remained on a

continuing basis. All other characters were seldom heard and gone

were Marjorie and her family as well as the studio audience, live

orchestra and original scripts.

Television

The radio show also suffered from the advent of television. A

televised version of the show, produced and syndicated by NBC (after

the pilot episode appeared twice on the network in late 1954), also

starring Waterman, premiered in 1955 but lasted only 39 episodes.

During that year, both the 15-minute radio show and the television

show were being produced simultaneously. The radio series was taped

on days when the TV production was inactive. Because of the grueling

schedule, quality suffered. Only a few examples of the quarter-hour

shows have survived. By the time the radio show entered its final

season, The Great Gildersleeve's remaining radio audience heard only

reruns of previous episodes.

The television series is considered now to be something of an insult

to the Great Gildersleeve legacy. Gildersleeve was sketched as less

lovable, more pompous and a more overt womanizer, an insult

amplified when Waterman himself said the key to the television

version's failure was its director not having known a thing about

the radio classic. Peary later appeared in the 1959 TV version of

Fibber McGee and Molly as Mayor LaTrivia. Fibber McGee and Molly

also failed to migrate to television in the 1950s without radio

stars Jim and Marion Jordan in the TV cast. Actress Barbara Stuart

landed her first television acting role on The Great Gildersleeve in

the role of Gildersleeve's secretary, Bessie.

Movies

After joining Jim and Marion Jordan (as Fibber McGee and Molly) and

fellow radio favorite Edgar Bergen in Look Who's Laughing (1941) and

Here We Go Again (1942), Peary finally received top billing for a

brief series of RKO films. The Great Gildersleeve (1942) also

carried Randolph from the radio cast to the screen, with Nancy Gates

as Marjorie and Freddie Mercer as Leroy. Walter Tetley, who played

Leroy on radio, could not be seen on screen as Leroy because he was

actually a child impersonator.

Gildersleeve on Broadway followed, in 1943; the story is centered on

Leroy as the odd boy out as everyone around him is falling in love.

Gildersleeve's Bad Day (1943) followed the mishaps around Gildy's

call to jury duty; and, Gildersleeve's Ghost (1944) brings Gildy's

relatives Randolph and Johnson up from the dead to help his campaign

for police commissioner.

Peary went on to continue his career (often billed as Hal Peary) in

films and television well into the 1970s. He died of a heart attack

in 1985.

Recordings

In full Gildersleeve character, at the height of the show's

popularity, Harold Peary recorded three albums, reading popular

children's stories for Capitol Records, in heavy-bookleted four-disc

78rpm record albums. Stories for Children, Told in His Own Way by

the Great Gildersleeve, was released in 1945 and was Capitol's

first-ever such release for children. With orchestral accompaniment,

it featured "Puss in Boots," "Rumpelstiltskin," and "Jack and the

Beanstalk." The second album, Children's Stories as Told by the

Great Gildersleeve, in 1946, featured "Hansel and Gretel" and "The

Brave Little Tailor," again with orchestral accompaniment. The third

and final album in the series, reverting to the title of the first

and released in 1947, included "Snow White and Rose Red" and

"Cinderella," once more with full orchestral accompaniment. The

music was by Robert Emmett Dolan. To make sure stories would be

unmistakably Gildersleevian without compromising their core

integrity, Capitol brought in The Great Gildersleeve's chief

writers, Sam Moore and John Whedon, to adapt them to Gildy's

unmistakable bearing.

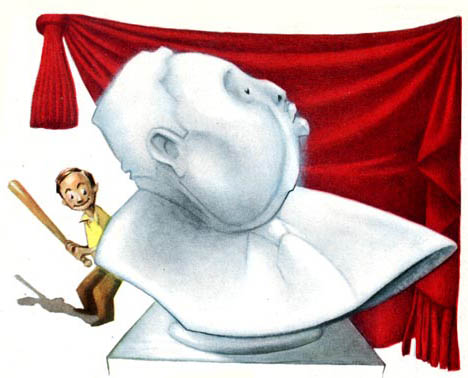

The Gildersleeve character was parodied in the 1945 Bugs Bunny

cartoon Hare Conditioned, in which the rabbit distracts a menacing

taxidermist by telling him that he sounds "just like that guy on the

radio, the Great Gildersneeze!" The taxidermist responds with "I

do?!" followed by Gildy's famous chuckle. The Gildersleeve voice in

this cartoon was done by radio actor and voice artist Dick Nelson.

|